‘Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity! We are happy in proportion to the things we can do without.’

About twelve miles north of where I live, in Concord, Massachusetts is a pond called Walden Pond. You may have heard of it. Its singular claim to fame is the part it played in the writer Henry David Thoreau’s life and work.

In 1845 Thoreau moved into a little one room cabin he built for himself on the northern shore of the pond. He live there for two years and two months and from that experience he eventually published a book titled Walden, now world-famous and recognized as an important work of American literature.

Today there is a replica of the cabin containing all the same things Thoreau had in the original: a fireplace, a bed, a desk, a table, and three chairs, ‘one for solitude, two for friendship, three for society.’

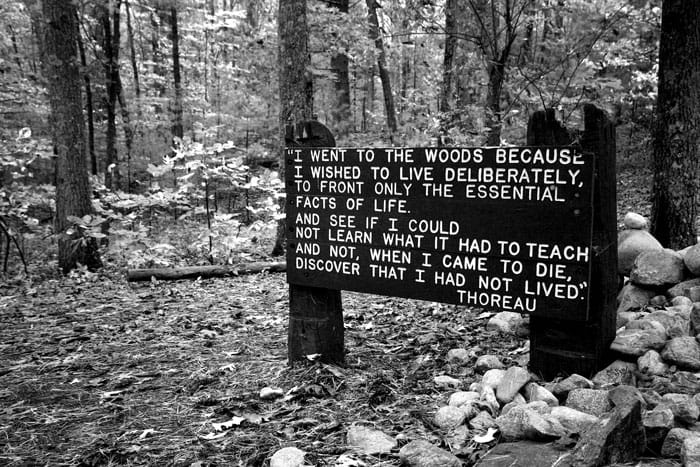

Walden Pond, a monument to Thoreau, and the replica of his cabin

In the chapter of Walden titled ‘Where I Lived, and What I Lived For,’ he explained his reason for the move:

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practise resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness to the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give a true account of it in my next excursion.

Thoughts on clothing and fashion

Thoreau had strong opinions on the subject of fashion, which he touches on in the first few pages of Walden, in the chapter titled ‘Economy’:

I say, beware of all enterprises that require new clothes, and not rather a new wearer of clothes. If there is not a new man, how can the new clothes be made to fit? If you have any enterprise before you, try it in your old clothes.

…

Perhaps we should never procure a new suit, however ragged or dirty the old, until we have so conducted, so enterprised or sailed in some way, that we feel like new men in the old, and that to retain it would be like keeping new wine in old bottles. Our moulting season, like that of the fowls, must be a crisis in our lives.

…

I believe that all races at some seasons wear something equivalent to the shirt. It is desirable that a man be clad so simply that he can lay his hands on himself in the dark, and that he live in all respects so compactly and preparedly that, if an enemy take the town, he can, like the old philosopher, walk out the gate empty-handed without anxiety.

…

While a thick coat can be bought for five dollars, which will last as many years, thick pantaloons for two dollars, cowhide boots for a dollar and a half a pair, a summer hat for a quarter of a dollar, and a winter cap for sixty-two and a half cents, or a better be made at home at a nominal cost, where is he so poor that, clad in such a suit, of his own earning, there will not be found wise men to do him reverence?

…

When I ask for a garment of a particular form, my tailoress tells me gravely, “They do not make them so now,” not emphasizing the “They” at all, as if she quoted an authority as impersonal as the Fates, and I find it difficult to get made what I want, simply because she cannot believe that I mean what I say, that I am so rash.

…

Of what use this measuring of me if she does not measure my character, but only the breadth of my shoulders, as it were a peg to bang the coat on? We worship not the Graces, nor the Parcae, but Fashion. She spins and weaves and cuts with full authority. The head monkey at Paris puts on a traveller’s cap, and all the monkeys in America do the same. I sometimes despair of getting anything quite simple and honest done in this world by the help of men.

…

On the whole, I think that it cannot be maintained that dressing has in this or any country risen to the dignity of an art. At present men make shift to wear what they can get. Like shipwrecked sailors, they put on what they can find on the beach, and at a little distance, whether of space or time, laugh at each other’s masquerade. Every generation laughs at the old fashions, but follows religiously the new.

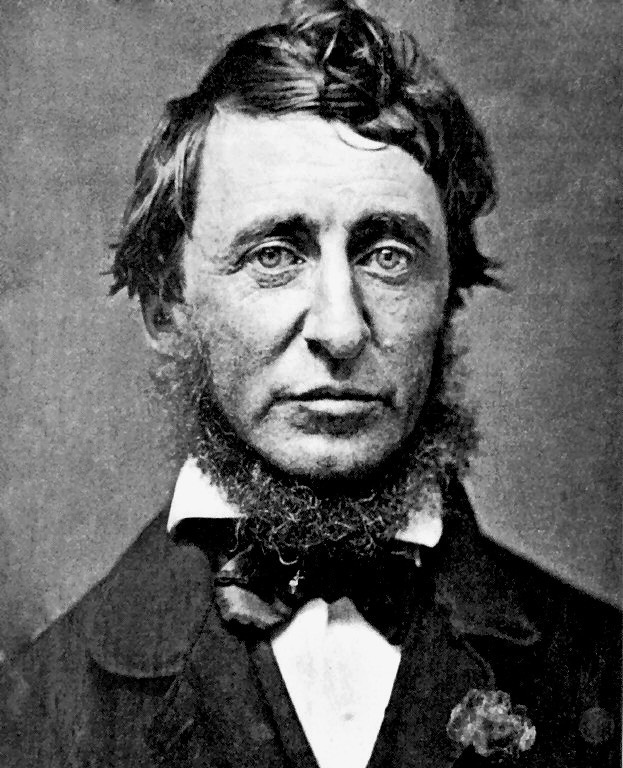

Thoreau’s own appearance, as reported by others

According to the Thoreau Reader, in 1842, after meeting Thoreau, Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote: ‘He is a singular character — a young man with much of wild original nature remaining in him; and so far as he is sophisticated, it is in a way and method of his own. He is ugly as sin, long-nosed, queer-mouthed, and with uncouth and somewhat rustic, although courteous manners, corresponding very well with such an exterior. But his ugliness is of an honest and agreeable fashion, and becomes him much better than beauty.’

In 1862, Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote of his friend: ‘He wore straw hat, stout shoes, strong gray trousers, to brave shrub-oaks and smilax, and to climb a tree for a hawk’s or a squirrel’s nest.’

Apparently the above photo of Thoreau (and from what I’ve seen, the most commonly found image of him), is one of ‘three daguerreotypes taken in June, 1856, when [he] was 39, after a Walden reader in Michigan had sent money and requested a picture. The beard had been grown the previous winter as a precaution against ‘throat colds” (also from the Thoreau Reader which references The Days of Henry Thoreau by Walter Harding for its information on Thoreau’s appearance).

Wikipedia’s entry on Thoreau had this fascinating bit to add: ‘[He] also wore a neck-beard for many years, which he insisted many women found attractive. However, Louisa May Alcott mentioned to Ralph Waldo Emerson that Thoreau’s facial hair ‘will most assuredly deflect amorous advances and preserve the man’s virtue in perpetuity.”

Top photo: Alex